The United States Vaccine Debate

Introduction

Vaccinations are artificial, immunological defense mechanisms used to defeat viruses that pose serious threats to the human immune system. Fortunately, there are successful vaccines for many deleterious viruses and diseases including influenza, hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella, and the varicella virus (Bezio et al., 51). Despite their success, vaccines and those who advocate for their use have recently come under extreme scrutiny, arising in what is now commonly known as the Vaccine Debate.

To foster a complete understanding of the circumstances leading up to this controversy, this essay will begin with an introduction to the history of vaccines from the late 1700s leading up to the ongoing anti-vaccination movement. This will lead into a thorough discussion of the rhetoric used by pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine protestors in response to California’s new mandatory vaccination law, Senate Bill 277. The rhetoric used by individuals on both sides of the protest often incorporates aspects of the American identity in their propaganda to incite American citizens to join their movement. Finally, examples of rhetorical artifacts used in the protests will be analyzed in relation to the American identity and the rhetorical strategies, ethos, pathos, and logos to point out the compelling aspects of both arguments.

The History of Vaccines

Vaccines became essential to survival with the impact of smallpox in Europe in the 1700s (Riedel). Smallpox is a deadly disease caused by the Variola virus that is characterized by skin rashes and fever (WebMD). Fortunately, those who witnessed the devastation of the disease in Europe came to realize that “survivors of smallpox became immune to the disease,” which eventually led to the practice of inoculation, the predecessor of vaccinations (Riedel). Inoculation is the unsettling practice of injecting “fresh matter taken from a ripe pustule of some person who suffered from smallpox” (Riedel) into the skin of a healthy individual. This preventative measure led to the development of the first smallpox vaccine by Edward Jenner in 1796 (Riedel). The idea behind vaccination is to prevent a disease or illness from occurring by intentionally introducing “dead or weakened forms of infectious microbes” (Williams, 8) into the body of a relatively healthy individual promoting the development of immunity (Williams, 8).

The practice of vaccination became widely successful in the early 1800s (Riedel), and vaccines eventually led to the abolishment of smallpox and highly reduced rates of other diseases “such as diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus” (Williams, 8). Vaccinations may have even gone so far as to influence the outcome of the Revolutionary War in the United States, with both sides of the war protecting their troops with vaccines (Jana). There is no doubt that the scope of survival from infectious diseases was heavily influenced by the faithful use of vaccinations. Global history has proven that previously deadly diseases such as smallpox have been completely overcome by the use of vaccines (Williams, 8). However, in recent years, the American public has shown fluctuations in their faith in vaccines, inspiring individuals to rally both against and in favor of immunizations.

The polarizing nature of the vaccine debate is most noticeable when the public responds to mandatory vaccination laws. In the 1905 Supreme Court case Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the Court ruled that “the board of health of a city or town” may “require and enforce the vaccination and revaccination of all the inhabitants thereof” in the interest of “public health or safety” (Justia). The defendant, Jacobson, was ruled against by the Court after declining to be vaccinated and was forced to pay a five dollar fine (Justia). The Court did implement exceptions, but the results of this case have continued to cause controversy in cities throughout the United States. On one side of the debate we see judicious lawmakers hoping to protect the majority, and on the other side concerned individuals are speaking out for personal freedoms.

Continuing such controversy, the state of California enacted Senate Bill 277 in February of 2015, making interesting changes to an existing vaccination law. The purpose of the bill was to “eliminate the exemption from immunization based on personal beliefs” (California Senate, 2015). The law does not legally require vaccinations, but it does require that all children be immunized before enrolling in daycare, public, or private schools in the state of California. As a result, “…hundreds of parents have attended public hearings to protest the measure, arguing that the state should not interfere with their decisions about what medical treatment to provide their children” (McGreevy).

The new law has also created dispute amongst proponents of the bill and religious institutions, such as the Nation of Islam (McGreevy). Personal belief exemptions previously allowed individuals to refuse vaccinations due to religious conflicts of interest (NCSL). Senate Bill 277 removes these exemptions and would force the hands of many anti-vaccine parents to immunize their children so they can attend school in California.

Laws such as Senate Bill 277 stir up emotions on behalf of two types of protestors: those who oppose the bill because it violates their personal beliefs and those who oppose the bill because they disapprove of vaccines altogether. The latter, often referred to as “anti-vaxxers” (Khazan), have developed an entire movement in opposition to mandatory vaccinations. This anti-vaccination movement, is a “rhetorical attempt…to arouse public opinion to the destruction or rejection…” (Griffin, 11) of vaccinations. Some of the credit for this movement can be given to former physician and current film director, Andrew Wakefield who published a paper in 1998 that provided false evidence of a correlation between autism and the MMR vaccine (Lipkin). Although the paper was discredited, the association between the disorder and the vaccine lingers eighteen years later (Lipkin).

The goal of the anti-vaccination movement is to maintain the right to deny mandatory vaccinations based on personal beliefs as well as to inform those who currently consent to vaccinations about the associated dangers. Their collective protest has developed from “a period of inception” to “a period of rhetorical crisis” (Griffin, 10). During the former period, Andrew Wakefield was spreading the message of the movement throughout the United Kingdom and the United States, causing panic amongst the parents of vaccinated children. The movement has since breached “rhetorical crisis” (Griffin, 10) because an unyielding conflict has arose between those who support the anti-vaccination movement and those who support vaccinations. Despite overwhelming evidence and support from the scientific community justifying the efficacy of vaccines (Williams, 9), rumors about the adverse effects of vaccines continue to circulate. The protest will only reach what Leland Griffin calls, “a period of consummation” when the protestors accept defeat or vaccine supporters concede to the protestor's wishes.

In contrast, there are many individuals and organizations that continue to advocate for the use of vaccinations despite backlash from angry parents and disgruntled religious institutions. To their dismay, the anti-vaccination movement has disseminated a plethora of misinformation to the American public. The individuals responsible for correcting this misinformation include, “…public health officials, the CDC, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Food and Drug Administration and child health advocates…” (Williams, 11).

The divide between pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine movements has created significant conflict amongst parents of school-aged children. This conflict is fueled by mandatory vaccination laws, which imply the state government’s explicit support of vaccinations. In the past, personal belief exemptions provided loopholes for parents who wished not to vaccinate their children. In fact, “up to 60 to 70 percent of parents,” in the Los Angeles area alone, used these exemptions to avoid immunizations for various personal reasons. Although many of these exemptions were valid, they defeated the purpose of vaccines, which are most effective when used in abundance. This is known as herd immunity, which suggests that vaccines need to be used by “92 percent or more of a population” (Khazan) to be truly successful. When applied, herd immunity protects even the unvaccinated “such as infants, pregnant women, or immunocompromised individuals” (vaccines.gov). Those children in Los Angeles schools who do become infected with preventable diseases will put other children at risk “by increasing their exposure” (Metcalf et al.). Therefore, as the anti-vaccination movement continues to grow, protection from infectious diseases through vaccination becomes less and less effective. Consequently, the outcome of this debate will have a profound impact on the spread of communicable diseases and the health of American citizens.

Rhetoric of the Vaccine Controversy

The anti-vaccination movement emerged amidst newfound information about the side effects of vaccines. It is widely known that vaccinations may cause “…soreness at the injection site, fever, aches, and fatigue” (Williams, 8). However, “Severe adverse effects, such as allergic reactions, convulsions, shock, and death are also possible but are reported to be statistically rare” (Williams, 8). These risks, on top of Andrew Wakefield’s false evidence of an association between autism and the MMR vaccine, may perplex concerned parents hoping to make the right decision for their child. With extensive evidence fueling the support of vaccinations as well as the elaborate warnings by anti-vaccination protestors, the decision to vaccinate or not to vaccinate can be difficult amidst all the contradictory guidance. However, as polarizing as this issue is, parents hoping to make the right choice for their children can find solace with their American values being represented on either side of the controversy.

Those who are anti-vaccine represent the right to have freedom over one’s body, which would seem an obvious right in America where personal freedom is so profoundly advertised. In many circumstances, personal beliefs are respected in the United States. For example, when a religious tradition calls for circumcision, or a Jehovah’s Witness patient denies a life-saving blood transfusion, we allow it. Both of these examples represent medically controversial issues in which Americans have ruled in favor of the individual’s rights whether they are asking for or refusing a particular treatment or procedure. However, other controversial medical procedures, such as abortions and now vaccines, have limitations that restrict personal freedom over one’s own body. In the United States, protesting against limitations is not uncommon. In fact, some may argue that protesting against limitations of personal freedoms is a crucial part of the American identity.

This conversation on protesting for personal freedoms prompts a discussion on the implications of mandatory vaccination laws on religious freedom in the United States. As previously discussed, the Nation of Islam has come forward objecting to the dismantling of personal belief exemptions. The United States is famously known as a melting pot of religiously diverse cultures that has fostered vast religious freedom. Some religions advocate for immunizations, while others, such as the Nation of Islam, oppose vaccination within their religious communities. However, it seems that the right to deny vaccinations based on religious beliefs has already been implicitly ruled on in the United States. In the 1994 Supreme Court Case Prince v. Massachusetts, the Court concluded, “the right to practice religion freely does not include liberty to expose the community or the child to communicable disease or the latter to ill health or death” (Cornell University Law School). We can conclude, therefore, that the American identity encompasses religious freedom, but only to the extent that American citizens are protected from the possible medical ramifications of various religious beliefs.

It is also an American characteristic to intervene in medical affairs for the greater good, as was displayed in 2014 with America’s involvement in the African Ebola crisis. By September of 2014, the United States had donated “more than $100 million” (Kaplan) to the cause on top of caring for four Ebola patients in U.S. hospitals (Kaplan). In the case of vaccines, the more individuals who are vaccinated, the more protected we are as a country. With this information in mind, we know that this is more than an individual issue. It is a national issue of immunological safety that is worth discussing as a country. Until this discussion leads to a more agreeable solution, mandatory vaccination laws will continue to be an example of United States intervening on behalf of the greater good.

With the breadth of the vaccine controversy expanding and the greater good of American citizens at stake, many intellectuals have taken it upon themselves to convince the public and parents of young children of the efficacy of vaccines through their work. In the first chapter of the book Vaccinations, Gretchen Flanders included the following “four-way stop sign” metaphor by Dr. Bruce Gellin, “‘A person who decides to ignore the stop sign knows he has less risk of an accident if others obey it. However, if two drivers make a similar decision, assuming that the other will stop, the outcome becomes much more risky for everyone in the intersection.’” (Flanders, 14). As more and more people make the decision to refuse vaccination, the risk for developing an infectious disease increases. Michelle Meadows, noted in her essayVaccines Are Safe and Effective, “…even immunized individuals can be at risk because no vaccine is ever 100 percent effective for everyone” (Meadows, 19).

Despite the many publications verifying the safety of vaccines, the anti-vaccination movement roars on, continuing to contribute to Senate Bill 277 protests in California. On May 16, 2015, protestors rallied at the doorstep of an event for the Democratic Party in Anaheim criticizing governor Jerry Brown for the bill’s passing (Jamison). Later that year, a Santa Monica ABC news station reported on an anti-vaccination protest labeled the Health Freedom Rally. Reporter Denise Dador claimed that “hundreds of parents and activists” were present at the event, as was Andrew Wakefield, an infamous promoter of the movement (Dador). The press and media coverage of these protests has helped spread anti-vaccine propaganda nationwide. With personal testimonies from parents establishing pathos and educated medical professionals providing a source ethos, the coercive anti-vaccine movement continues to gain followers.

The images of these protests on the news amplify the movement’s following key terms and phrases used to alarm the public: informed consent, autism, and my child, my choice. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, informed consent is a participant’s agreement to participant in research once informed of all possible risks (hhs.gov). By using this phrase, protestors are eliciting their right to know all possible side effects of vaccines as well as their right to refuse them.

The second key term used in anti-vaccination protests is autism. Despite evidence disproving the association between autism and vaccination, protestors continue to use this word as a rhetorical strategy. By putting the word “autism” on their posters, protestors use pathos, persuasion through emotion, to persuade other parents to avoid vaccines. Jenny McCarthy, a celebrity representative of the anti-vaccination movement, has used this word continuously to criticize vaccinations. As she personally has a child with autism, McCarthy is essential to the effective use of pathos in this movement (Coombes).

Finally, the phrase “my child, my choice” is seen all over anti-vaccine posters. This phrase suggests that the new law revokes a parent’s choice to not vaccinate their children. In actuality, parents still have the right to refuse to vaccinate their children. The penalty of this choice, however, is that their child will no longer be able to attend daycare, public, or private school facilities (SB 277). This penalty may put many parents in a situation where vaccination is now a financial dilemma rather than a healthcare dilemma.

A 2005 study by Allison Kennedy, Cedric Brown, and Deborah A. Gust, found that “parents who reported lower household income were more likely to be opposed to compulsory vaccination…” (Kennedy, et al.). Therefore, on top of the medical outcomes of the vaccine controversy, there are significant economic outcomes as well. According to the study, “parents with lower household incomes are more likely to experience barriers, such as transportation or access to health care services” (Kennedy et al.). These results present interesting questions to those in favor of vaccinations. First of all, are vaccines easy enough to receive? If parents cannot physically get their children to a vaccination location, we cannot expect their children to be vaccinated. Second, we must ask if vaccines pose significant financial costs to less wealthy American families. Will these mandatory vaccines be provided free of cost? With the passing of Senate Bill 277 in California, questions like this need to be thoroughly investigated because the debate now clearly concerns more than just anti-vaccine and pro-vaccine arguments. There is a substantial economic perspective that still needs to be addressed.

Unfortunately, the authors of the bill failed to use specific language regarding how California citizens will access these mandatory vaccines. The bill simply states that California school districts will have the ability to “use funds, property, and personnel of the district” to help immunize school children (SB 277). Therefore, it is not legally required for the district to financially sponsor the immunization of California school children, and the costs may indeed fall to their parents.

The financial and medical concerns of worried parents feed into the success of the anti-vaccination movement. The movement’s rhetorical goal is to use these concerns to affect a change in the national opinion on vaccines through celebrity endorsements and by pulling on heartstrings. There is no doubt that the use of ethos and pathos within the anti-vaccination movement has benefited their argument. With celebrities like Jenny McCarthy speaking at protests and rallies, the movement’s protests attract bigger crowds and seem more substantial in news reports. The existing political and legislative pursuits are deeply connected to the movement’s rhetorical goal. As previously discussed, the protestors in this movement seek to repeal mandatory vaccination laws, such as Senate Bill 277, to ensure that personal belief exemptions remain legal loopholes available to refuse vaccinations. More broadly speaking, these protestors hope to create political change by limiting the government’s control over vaccines and increasing medical autonomy.

The individuals involved in the anti-vaccination movement speak on behalf of identities they feel connected to, including low-income families with limited medical access, concerned parents, and American patriots fighting to preserve individual liberties. This last identity, the American identity, is heavily represented on both sides of the debate in the images, slogans, and testimonies of vaccine activists and protestors.

Protest Artifacts from the Vaccine Debate

The Anti-vaccination movement may have gained its traction in the United States because the core of the protest encompasses many attractive components of the American identity. The protests in California concerning the recent passing of Senate Bill 277 elicited the creation of new slogans in support of the movement. The most coercive of which is the slogan “If there is a risk, there must be a choice.” This slogan has no clear author, but rings with American patriotism. Those who use this slogan are referring to the proposed risks involved with vaccinations, especially in children. This slogan is credible amongst American citizens, because in most risky circumstances, we are promised a choice. When it comes to smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol, for example, adult Americans are given the choice not to engage in these risky behaviors. Anti-vaccination protestors advocate for this same liberty to refuse vaccines that they believe come with unjustified risks. Those who profess this slogan are demanding that government officials intervene on behalf of concerned citizens who refuse to take part in what they believe to be a risky endeavor.

When a law such as Senate Bill 277 creates this much public outcry, people tend to approach government officials pleading for an appeal. California resident, Laura Hayes, is one such individual. In an open letter to California state senator, Ted Gaines, Laura Hayes wrote:

“SB 277 removes all non-medical exemptions for state-mandated vaccines. One need only back it up one step further to see that mandates in and of themselves are not in alignment with the U.S. Constitution, nor with the international code of ethics found in The Nuremberg Code, nor with the ethical practice of medicine which requires prior, voluntary, and informed consent.”

The reference to the United States Constitution, a document that upholds many fundamental American values, represents a powerful use of ethos in her argument. To this day, American citizens regard the document with profound reverence. More than two hundred years after the creation of the Constitution, it means something to defend the rights that it promised. By referencing the Constitution, Hayes directly questions the legitimacy of Senate Bill 277.

Also in Hayes’ statement, we see a key phrase of the anti-vaccination movement previously discussed, “informed consent” (Hayes). As a society, we place a great deal of trust in physicians and organizations like the Center for Disease Control (CDC) to make knowledgeable decisions about the healthcare that is made available to us. However, Hayes is claiming that a patient’s consent is just as vital to any medical procedure as it is when administering vaccines. She does so by directly referencing the Nuremberg Code, which states, “voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential” to be involved in medical experiments (hhs.gov). Medical experimentation often has a negative association, and Hayes is tying that negative association to vaccinations.

Hayes intentionally alluded to the Nuremberg Code and the U.S. Constitution to provide a source of ethos in her declaration against mandatory vaccination laws. Similarly, anti-vaccination campaigns use ideas fundamental to the idea of being American to market their negativity about vaccines.

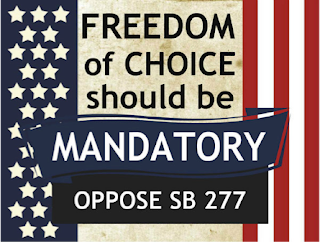

Image credit: parentsrightscalifornia.weebly.com

The image shown above was published on the website for the California Coalition for Vaccine Choice. This artifact immediately directs reader’s attention to a sacred symbol of American patriots, the American flag. The flag itself is emblematic of American triumph and creates strong emotions. It was raised after the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. It is flown outside the United States Capitol building and throughout our nation’s capitol. It distinguishes American citizens from athletes from around the world during the Olympics. The background chosen in the image above is an example of pathos, because the American flag has incredible sentimental value in this country.

Additionally, this image uses a word that is quintessential to the American identity –“freedom.” It is worth noting here that although freedom is abundant in this country, it is not absolute throughout the world. It is a privilege that American citizens honor by paying respects to the American soldiers and the American flag. Lee Greenwood captures this spirit in the following lyrics of his song God Bless the USA: “I’m proud to be an American, where at least I know I’m free. And I won’t forget the men who died, who gave that right to me” (scoutsongs.com).

Finally, this image uses the word “mandatory.” This word was specifically chosen to use the language of Senate Bill 277 against mandatory vaccine advocates (leginfo.ca.gov). The image reads, “Freedom of choice should be mandatory.” The wording of this image promotes the idea that instead of mandating vaccinations, the state of California should mandate that every citizen be given a choice about whether or not to utilize immunizations. The language of this slogan is not necessarily catchy or easy to chant during a protest, which limits its credibility in the movement. Additionally, one must recognize the language of the Senate Bill to truly comprehend the message of the slogan. However, for those who are familiar with the senate bill, the most compelling aspect of this image is that the ad does not need to use the word “vaccination” to capture the anti-vaccination movement. There is no mention of vaccinations because it has been figuratively ripped from its association with the word “mandatory,” and replaced with “freedom of choice.”

On the other half of the Vaccine Debate, pro-vaccine activists have utilized their own protest artifacts to foster faith in science and vaccines. A member of UNICEF, Anthony Lake, captured an important piece of the pro-vaccine movement in the following statement of a keynote speech from 2011: “Every child has a fundamental right to survive, to thrive and to grow. It should enrage us all that something as relatively inexpensive, easy to deliver and effective as routine vaccination is still not reaching the places where it can do the most good, and save the most children” (Lake).

In the Preamble of the Constitution, the government promises to “promote the general Welfare” (archives.gov), and Lake’s statement prompts the international community to do the same. The various diseases that vaccines can prevent are “…a major risk to the health and welfare of human populations…” (Sun et al., 114), so it makes sense to promote the use of vaccines. The vaccinations for several common diseases have prevented “around six million annual deaths globally” (Sun et al., 14). In light of this worrisome statistic, it is clear why Anthony Lake would advocate for “routine vaccination” (Lake).

The language of this segment of his speech vividly evokes pathos because he references the lives of young, vulnerable children. When a child’s life is implicated by our decisions, people tend to listen. Additionally, Lake defends these “relatively inexpensive” (Lake) vaccines as safe methods of preventing diseases. This introduces a hint of logos into his argument because he relies upon the factual financial and medical data regarding vaccines to support his pro-vaccine stance in the debate. He alludes to illogical reasons why vaccinations have not been used to their full potential.

Although Anthony Lake’s position at UNICEF certainly heightened his credibility as a spokesperson for vaccines, parents of children who had adverse affects to vaccinations provide the most ethos to the pro-vaccine movement. For example, Emily West, a mother whose son had adverse affects after being vaccinated, proclaimed her pro-vaccination stance in a CNN interview with Jareen Imam: “‘At least try to vaccinate…I have tried, and I did it because it is part of my civic duty.’” (qtd. Imam).

Emily West’s use of the phrase “civic duty” is a compelling use of pathos because American citizens have been taught not to take civic duties lightly. By elevating the practice of vaccination to the same level as “…obeying the laws of the country, paying taxes levied by the government, or serving on a jury…” (Liverpool), we assume that American citizens will comply with the best of their ability. Laws, taxes, and juries are created in the interest of the society as a whole. Similarly, vaccines are used in the interest of not only those who are vaccinated, but also those who cannot be vaccinated due to other health concerns.

Mandatory vaccination laws, such as Senate Bill 277, create “a protective effect called herd immunity that interrupts the spread of the virus to vulnerable people” (Hensley). Carl Krawitt, another concerned parent whose child cannot be immunized, is also in favor of vaccinations (Aliferis). His son, Rhett, suffered from leukemia at an early age and now “depends on everyone around him for protection” (Aliferis). With individuals like Krawitt and West advocating for their child’s lives and vaccinations simultaneously, it is easy to see how pathos can be incorporated into the rhetoric of both sides of the controversy.

The issue surrounding the vaccination debate is that people on both sides are interested in advocating for a worthy cause, child safety. Although the evidence overwhelmingly supports vaccinations, the United States is a democracy and people have the right to openly protest against them (Jana et al.). The Anti-Vaccination movement has managed to utilize both ethos and pathos in their campaign to repeal mandatory vaccination laws. Backed by Jenny McCarthy and Andrew Wakefield, the movement has captured our attention by purporting an association between vaccines and autism as well as various other conspiracies. In contrast, those who continue to advocate for vaccines have science and factual data in their favor, with many physicians, child cancer survivors, and statistics in support of vaccines.

Conclusion

Although injecting oneself with a potentially hazardous virus does not seem intuitively beneficial, the almost certain guarantee of longstanding immunity makes vaccines worth the risk. The complicated history of vaccinations has shown us that “public fear of disease is often replaced by fear of preventative intervention as soon as the disease itself begins to fade from collective memory” (Jana et al.). This phenomenon has created a plague of conflicting opinions in this country that, if allowed to continue, may foster the development of actual plagues.

Senate Bill 277 was the California state government’s attempt to quell this immunization conflict, but has so far been counterproductive. While students in California will be required to get vaccinated this year, anti-vaccine parents continue to object to the law and the anti-vaccination movement grows stronger. The protests through this movement have been highly legible to the public, which has kept American citizens aware of the debate and has encouraged them to take a stance. While many Americans choose an anti-vaccine stance, it seems that the California state government, a famously liberal state, has ruled in favor of government regulation of vaccines. The protest is still firmly rooted in a period of “rhetorical crisis” (Griffin, 11), so it is difficult to determine if anti-vaccination protests will prove successful. At this point, medical evidence and laws like Senate Bill 277 suggest that the protest will, in the end, be a futile attempt to delegitimize vaccines.

Despite the limited legal implications of the anti-vaccination movement, this polarizing issue continues to draw public attention. Last year in a GOP debate, current Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump re-ignited the discussion on autism and vaccines and took a definitively anti-vaccine stance (Miller). If Donald Trump is elected this November, the anti-vaccination movement may see some success after all.

More recently, the anti-vaccination movement has garnered the spotlight through the release of Andrew Wakefield’s new documentary “Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe.” The film was scheduled to debut at the Tribeca Film Festival this month, but was removed due to the perceived negative message of the film (Lipkin). The existence of this film alone, however, is enough to concern pro-vaccine activists because it is a sign that the anti-vaccination movement continues on.

Unfortunately, Andrew Wakefield and other members of the movement are within their legal rights to protest vaccines through artifacts like this documentary, and we can expect these protests to continue in the future. In order to combat the dispersal of further anti-vaccine propaganda, pro-vaccine advocates must continue to advocate for legal protection. Until the country can come to a consensus on vaccines, it is likely that this intensely debated issue will continue to cause conflict in the United States.

Works Cited

Aliferis, Lisa. “To Protect His Son, A Father Asks School To Bar Unvaccinated Children.” npr.org. 27 January 2015. Web. 14 April 2016.

“California Senate Bill 277.” leginfo.ca.gov. 19 February 2015. Web. 5 April 2016.

“Community Immunity (“Herd Immunity”).” vaccines.gov. 3 March 2016. Web. 23 April 2016.

Constitution Quotes. brainyquote.com. Web. 14 April 2016.

Coombes, Rebecca. "VACCINE DISPUTES." BMJ: Britsih Medical Journal 338.7710 (2009): 1528-1531. Web. 04 April 2016.

Dador, Denise. “Hundreds Protest California Vaccine Bill In Santa Monica.” abc7.com. 03 July 2015. Web. 07 April 2016.

Flanders, Gretchen. “Vaccinations Under Scrutiny: An Overview.” Vaccinations. Ed. Mary E. Williams. Farmington Hills: Greenhaven Press, 2003. pgs. 12-17. Print. 07 April 2016.

“Frequently Asked Questions About Human Research.” HHS.gov. Web. 07 April 2016.

Greenwood, Lee. “God Bless The USA.” scoutsongs.com. Web. 14 April 2016.

Griffin, Leland M. “The Rhetoric of Historical Movements.” Readings on the Rhetoric of Social Protest. By Chlares E. Morris III and Stephen H. Brown. 3rd ed. 183-203. Desire 2 Learn. Web. 07 April 2016.

Hayes, Laura. Letter to Senator Gaines. California Coalition for Vaccine Choice. 20 March 2015. Web. 14 April 2016.

Hensley, Scott. “Vaccination Gaps Helped Fuel Disneyland Measles Spread.” npr.org. 16 March 2015. Web. 4 April 2016.

Imam, Jareen. “Parents to parents: Vaccinating is personal.” CNN. 7 February 2015. Web. 14 April 2016.

“Jacobson v. Massachusetts.” US Supreme Court, Justia (1905). Web. 5 April 2016

Jana, Laura A. June E. Osborn. “The History of Vaccine Challenges: Conquering Diseases, Plagued by Controversy.” Vaccinophobia and Vaccine Controversies of the 21st Century. pgs. 1-13. 27 May 2013. Web. 7 April 2016.

Jamison, Peter. “Vaccinatio protestors at Democratic convention compare California to Nazi Germany.”The Los Angeles Times. 16 May 2015. Web. 07 April 2016.

Liverpool, Nicholas J.O. “Civil Rights, Civic Duties and Responsibilities.” Government of the Commonwealth of Dominca, Office of the President. Web. 14 April 2016.

McGreevy, Patrick. “Nation of Islam Opposes California Vaccine Mandate Bill.” The Los Angeles Times. 22 June 2015. 9 March 2016.

Meadows, Michelle. “Vaccines Are Safe and Effective.” Vaccinations. Ed. Mary E. Williams. Farmington Hills: Greenhaven Press, 2003. pgs. 18-25. Print. 07 April 2016.

Kaplan, Rebecca. “Obama to boost U.S. involvement in fight against Ebola.” CBS News. 15 September 2014. Web. 07 April 2016.

Kennedy, Allison M., Cedric J. Brown, and Deborah A. Gust. “Vaccine beliefs of parents who oppose compulsory vaccination.” Public Health Reports 120.3 (2005): 252-258. Web. 03 April 2016.

Khazan, Olga. “Wealthy L.A. Schools’ vaccination Rates Are as Low as South Sudan’s.” theatlantic.com. 16 September 2014. Web. 5 April 2016. (Popular Source)

Lake, Anthony. “Reaching the Fifth Child: Immunization and Equity.” UNICEF Institute of Medicine Annual Meeting, Washington D.C. 17 October 2011. Keynote Speech. unicef.org. Web. 14 April 2016.

Lipkin, W. Ian. “Anti-Vaccination Lunacy Won’t Stop.” The Wall Street Journal. 3 April 2016. Web. 07 April 2016.

Miller, Michael E. “The GOP’s dangerous ‘debate’ on vaccines and autism.” The Washington Post. 17 September 2015. Web. 27 April 2016.

“Prince v. Massachusetts.” Cornell University Law School. Web. 23 April 2016.

Riedel, Stefan. “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination.” Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 18.1 (2005): 21–25. Print.

“Smallpox.” WebMD. 23 April 2015. Web. 6 April 2016.

Sun, Chengjun. Wei Yang. “Impact of Vaccination on Disease Prevention and Control.” Immunology and Immune System Disorders: Vaccinations: Procedures, Types and Controversy. Adeline I. Bezio and Braydon E. Campbell. New York, NY: Nova Biomedical, (2012). 49-74. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 14 April 2016.

“States With Religious and Philosophical Exemptions From School Immunization Requirements.” National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). 21 January 2016. Web. 23 April 2016.

The Nuremberg Code. hhs.gov. Web. 14 April 2016.

Williams, Mary E., ed. Vaccinations. Farmington Hills: Greenhaven Press, 2003. Print. 4 April 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment